Code

!pip install dldna[colab] # in Colab

# !pip install dldna[all] # in your local

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2“There is a bigger difference between theory and practice than between theory and theory.” - Yann LeCun, 2018 Turing Award winner

The success of deep learning models heavily depends on effective optimization algorithms and proper weight initialization strategies. This chapter delves into the core elements of deep learning model training, namely optimization and initialization methods, and presents ways to intuitively understand these processes through visualization. First, it explores the development and mathematical principles of various weight initialization methods that form the foundation of neural network learning. Then, starting with Gradient Descent, it compares and analyzes the working principles and performance of state-of-the-art optimization algorithms such as Adam, Lion, Sophia, and AdaFactor. In particular, it not only discusses theoretical backgrounds but also experimentally verifies how each algorithm operates in actual deep learning model training processes. Finally, it introduces various techniques for visualizing and analyzing high-dimensional loss function spaces (loss landscapes) and provides in-depth insights into the learning dynamics of deep learning models.

Neural network parameter initialization is a crucial element that determines the model’s convergence, learning efficiency, and final performance. Incorrect initialization can be a primary cause of training failure. PyTorch provides various initialization methods through the torch.nn.init module, with detailed information available in the official documentation. The evolution of initialization methods reflects the history of deep learning researchers overcoming the difficulties of neural network learning. In particular, inappropriate initialization has been identified as a major obstacle to deep neural network learning, causing vanishing or exploding gradient phenomena. Recently, the emergence of large language models such as GPT-3 and LaMDA has further emphasized the importance of initialization. As model sizes increase, the distribution of initial parameters has a greater impact on the early stages of training. Therefore, selecting an appropriate initialization strategy tailored to the model’s characteristics and size has become an essential step in developing deep learning models.

The development of neural network initialization methods is the result of in-depth mathematical theory and numerous experimental validations. Each initialization method was designed to address specific problem situations (e.g., using certain activation functions, network depth, or model type) or improve learning dynamics, evolving over time to respond to new challenges.

The following are the initialization methods that will be compared and analyzed in this book. (The complete implementation code is included in the chapter_04/initialization/base.py file.)

!pip install dldna[colab] # in Colab

# !pip install dldna[all] # in your local

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import numpy as np

# Set seed

np.random.seed(7)

torch.manual_seed(7)

from dldna.chapter_05.initialization.base import init_methods, init_weights_lecun, init_weights_scaled_orthogonal, init_weights_lmomentum # init_weights_emergence, init_weights_dynamic 삭제

init_methods = {

# Historical/Educational Significance

'lecun': init_weights_lecun, # The first systematic initialization proposed in 1998

'xavier_normal': nn.init.xavier_normal_, # Key to the revival of deep learning in 2010

'kaiming_normal': nn.init.kaiming_normal_, # Standard for the ReLU era, 2015

# Modern Standard

'orthogonal': nn.init.orthogonal_, # Important in RNN/LSTM

'scaled_orthogonal': init_weights_scaled_orthogonal, # Optimization of deep neural networks

# 2024 Latest Research

'l-momentum': init_weights_lmomentum # L-Momentum Initialization

}L-Momentum Initialization (Zhuang, 2024)

\(W \sim U(-\sqrt{\frac{6}{n_{in}}}, \sqrt{\frac{6}{n_{in}}})\) \(W = W \cdot \sqrt{\frac{\alpha}{Var(W)}}\)

where \(U\) is the uniform distribution, and \(\alpha\) represents the L-Momentum value, using the square of the momentum value used in the optimizer.

Most modern initialization methods follow these three core principles (either explicitly or implicitly):

Variance Preservation: The variance of activation values during the forward pass and gradients during the backward pass should be maintained consistently across layers.

\(Var(y) \approx Var(x)\)

This helps in stable learning by preventing signals from becoming too large or too small.

Spectral Control: The distribution of singular values of weight matrices should be controlled to ensure numerical stability during training.

\(\sigma_{max}(W) / \sigma_{min}(W) \leq C\)

This is particularly important in structures like recurrent neural networks (RNNs), where weight matrices are repeatedly multiplied.

Expressivity Optimization: The effective rank of the weight matrix should be maximized to ensure that the network has sufficient expressiveness. \(rank_{eff}(W) = \frac{\sum_i \sigma_i}{\max_i \sigma_i}\) Recent studies have been trying to explicitly satisfy these principles.

In conclusion, the initialization method should be carefully chosen considering the model’s size, structure, activation function, and interaction with the optimization algorithm, as it has a significant impact on the model’s learning speed, stability, and final performance.

As the depth of a neural network increases, preserving the statistical characteristics (especially variance) of signals during forward propagation and backpropagation is crucial. This prevents signals from vanishing or exploding, enabling stable learning.

Let \(h_l\) be the activation value of the \(l\)th layer, \(W_l\) be the weight matrix, \(b_l\) be the bias, and \(f\) be the activation function. Then, the forward propagation can be expressed as:

\(h_l = f(W_l h_{l-1} + b_l)\)

Assuming that each element of the input signal \(h_{l-1} \in \mathbb{R}^{n_{in}}\) is an independent random variable with a mean of 0 and variance \(\sigma^2_{h_{l-1}}\), each element of the weight matrix \(W_l \in \mathbb{R}^{n_{out} \times n_{in}}\) is an independent random variable with a mean of 0 and variance \(Var(W_l)\), and the bias \(b_l = 0\), the following holds when the activation function is linear:

\(Var(h_l) = n_{in} Var(W_l) Var(h_{l-1})\) (where \(n_{in}\) is the input dimension of the \(l\)th layer)

For the variance of the activation value to be preserved, \(Var(h_l) = Var(h_{l-1})\) must hold, so \(Var(W_l) = 1/n_{in}\) must be true.

During backpropagation, for the error signal \(\delta_l = \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_l}\) (where \(L\) is the loss function), the following relationship holds:

\(\delta_{l-1} = W_l^T \delta_l\) (assuming the activation function is linear)

Therefore, to preserve variance during backpropagation, \(Var(\delta_{l-1}) = n_{out}Var(W_l)Var(\delta_l)\) must hold, so \(Var(W_l) = 1/n_{out}\) must be true. (where \(n_{out}\) is the output dimension of the \(l\)th layer)

ReLU Activation Function

The ReLU function (\(f(x) = max(0, x)\)) tends to reduce the variance of the activation value because it sets half of the input to 0. Kaiming He proposed a variance preservation formula to compensate for this:

\(Var(W_l) = \frac{2}{n_{in}} \quad (\text{ReLU-specific})\)

This compensates for the reduction in variance by increasing it by a factor of 2.

Leaky ReLU Activation Function

For Leaky ReLU (\(f(x) = max(\alpha x, x)\), where \(\alpha\) is a small constant), the generalized formula is:

\(Var(W_l) = \frac{2}{(1 + \alpha^2) n_{in}}\)

There is also a method to initialize using the inverse of the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM), which contains curvature information in parameter space, allowing for more efficient initialization. (For more details, refer to reference [4] Martens, 2020).

The singular value decomposition (SVD) of a weight matrix \(W \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}\) is expressed as \(W = U\Sigma V^T\), where \(\Sigma\) is a diagonal matrix and its diagonal elements are the singular values (\(\sigma_1 \geq \sigma_2 \geq ... \geq 0\)) of \(W\). If the maximum singular value (\(\sigma_{max}\)) of the weight matrix is too large, it can cause an exploding gradient, and if the minimum singular value (\(\sigma_{min}\)) is too small, it can cause a vanishing gradient.

Therefore, controlling the ratio of singular values (condition number) \(\kappa = \sigma_{max}/\sigma_{min}\) is important. The closer \(\kappa\) is to 1, the more stable the gradient flow is guaranteed.

Theorem 2.1 (Saxe et al., 2014): In a deep linear neural network with orthogonal initialization, if the weight matrix \(W_l\) of each layer is an orthogonal matrix, the Frobenius norm of the Jacobian matrix \(J\) of the output with respect to the input is maintained as 1.

\(||J||_F = 1\)

This helps alleviate the problem of gradient disappearance or explosion even in very deep networks.

Miyato et al.(2018) proposed a spectral normalization technique that restricts the spectral norm (maximum singular value) of the weight matrix to improve the stability of GAN training.

\(W_{SN} = \frac{W}{\sigma_{max}(W)}\)

This method is particularly effective in GAN training and has recently been applied to other models such as Vision Transformer.

The diversity of features that a weight matrix \(W\) can express can be measured by the uniformity of the singular value distribution. The effective rank is defined as follows.

\(\text{rank}_{eff}(W) = \exp\left( -\sum_{i=1}^r p_i \ln p_i \right) \quad \text{where } p_i = \frac{\sigma_i}{\sum_j \sigma_j}\)

Here, \(r\) is the rank of \(W\), \(\sigma_i\) is the \(i\)-th singular value, and \(p_i\) is the normalized singular value. The effective rank is an indicator of the distribution of singular values, and a larger value means that the singular values are more evenly distributed, indicating higher expressivity.

| Initialization Method | Singular Value Distribution | Effective Rank | Suitable Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xavier | Decreases relatively quickly | Low | Shallow MLP |

| Kaiming | Adjusted for ReLU activation (decreases less) | Medium | CNN |

| Orthogonal | All singular values are 1 | High | RNN/Transformer |

| Emergence-Promoting | Adjusts according to network size, decreases relatively slowly (close to heavy-tailed distribution) | High | LLM |

Emergence-Promoting initialization is a recently proposed technique to promote emergent abilities in large language models (LLMs). This method adjusts the variance of the initial weights according to the network size (especially the depth of the layers), which has the effect of increasing the effective rank.

Chen et al. (2023) proposed the following scaling factor \(\nu_l\) for Transformer models:

\(\nu_l = \frac{1}{\sqrt{d_{in}}} \left( 1 + \frac{\ln l}{\ln d} \right)\)

where \(d_{in}\) is the input dimension, \(l\) is the layer index, and \(d\) is the model depth. This scaling factor is multiplied by the standard deviation of the weight matrix to initialize it. Specifically, it samples from a normal distribution with a standard deviation of \(\sqrt{2/n_{in}}\) multiplied by \(\nu_l\).

The Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) theory proposed by Jacot et al. (2018) is a useful tool for analyzing the learning dynamics of “infinitely wide” neural networks. According to NTK theory, the expected Hessian matrix of a very wide neural network at initialization is proportional to the identity matrix. Specifically,

\(\lim_{n_{in} \to \infty} \mathbb{E}[\nabla^2 \mathcal{L}] \propto I\) (at initialization)

This suggests that Xavier initialization provides nearly optimal initialization for wide neural networks.

Recent studies such as MetaInit (2023) propose learning the optimal initialization distribution for a given architecture and dataset through meta-learning.

\(\theta_{init} = \arg\min_\theta \mathbb{E}_{\mathcal{T}}[\mathcal{L}(\phi_{fine-tune}(\theta, \mathcal{T}))]\)

where \(\theta\) is the initialization parameter, \(\mathcal{T}\) is the training task, and \(\phi\) represents the process of fine-tuning a model initialized with \(\theta\).

Recently, initialization methods inspired by principles in physics have also been studied. For example, methods that mimic the Schrödinger equation in quantum mechanics or the Navier-Stokes equations in fluid dynamics to optimize inter-layer information flow have been proposed. However, these methods are still in the early stages of research and their practicality has not been verified.

To investigate how the various initialization methods actually affect model learning, we will conduct a comparative experiment using a simple model. We will train models with each initialization method under the same conditions and analyze the results. The evaluation metrics are as follows.

| Evaluation Metric | Meaning | Desirable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Error Rate(%) | Final model’s predictive performance (lower is better) | Lower is better |

| Convergence Speed | Learning curve’s slope (learning stability indicator) | Lower (steeper) is faster convergence |

| Average Condition Number | Numerical stability of weight matrix | Lower (closer to 1) is more stable |

| Spectral Norm | Size of weight matrix (maximum singular value) | Needs an appropriate value, not too large or small |

| Effective Rank Ratio | Expressiveness of weight matrix (uniformity of singular value distribution) | Higher is better |

| Execution Time(s) | Learning time | Lower is better |

from dldna.chapter_04.models.base import SimpleNetwork

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_data_loaders, get_device

from dldna.chapter_05.initialization.base import init_methods

from dldna.chapter_05.initialization.analysis import analyze_initialization, create_detailed_analysis_table

import torch.nn as nn

device = get_device()

# Initialize data loaders

train_dataloader, test_dataloader = get_data_loaders()

# Detailed analysis of initialization methods

results = analyze_initialization(

model_class=lambda: SimpleNetwork(act_func=nn.PReLU()),

init_methods=init_methods,

train_loader=train_dataloader,

test_loader=test_dataloader,

epochs=3,

device=device

)

# Print detailed analysis results table

create_detailed_analysis_table(results)

Initialization method: lecun/home/sean/Developments/expert_ai/books/dld/dld/chapter_04/experiments/model_training.py:320: UserWarning: std(): degrees of freedom is <= 0. Correction should be strictly less than the reduction factor (input numel divided by output numel). (Triggered internally at ../aten/src/ATen/native/ReduceOps.cpp:1823.)

'std': param.data.std().item(),

Initialization method: xavier_normal

Initialization method: kaiming_normal

Initialization method: orthogonal

Initialization method: scaled_orthogonal

Initialization method: l-momentumInitialization Method | Error Rate (%) | Convergence Speed | Average Condition Number | Spectral Norm | Effective Rank Ratio | Execution Time (s)

---------------------|--------------|-----------------|------------------------|-------------|--------------------|------------------

lecun | 0.48 | 0.33 | 5.86 | 1.42 | 0.89 | 30.5

xavier_normal | 0.49 | 0.33 | 5.53 | 1.62 | 0.89 | 30.2

kaiming_normal | 0.45 | 0.33 | 5.85 | 1.96 | 0.89 | 30.1

orthogonal | 0.49 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 30.0

scaled_orthogonal | 2.30 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.95 | 30.0

l-momentum | nan | 0.00 | 5.48 | 19.02 | 0.89 | 30.1The results of the experiment are summarized in the following table.

| Initialization Method | Error Rate (%) | Convergence Speed | Average Condition Number | Spectral Norm | Effective Rank Ratio | Execution Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lecun | 0.48 | 0.33 | 5.66 | 1.39 | 0.89 | 23.3 |

| xavier_normal | 0.48 | 0.33 | 5.60 | 1.64 | 0.89 | 23.2 |

| kaiming_normal | 0.45 | 0.33 | 5.52 | 1.98 | 0.89 | 23.2 |

| orthogonal | 0.49 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 23.3 |

| scaled_orthogonal | 2.30 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.95 | 23.3 |

| l-momentum | nan | 0.00 | 5.78 | 20.30 | 0.89 | 23.2 |

Notable points from the experiment results are as follows.

Excellent performance of Kaiming initialization: Kaiming initialization showed the lowest error rate at 0.45%. This result demonstrates the optimal combination with ReLU activation functions and reconfirms that Kaiming initialization is effective when used with ReLU series functions.

Stability of Orthogonal series: Orthogonal initialization showed the best numerical stability with a condition number of 1.00. This means that gradients are not distorted and propagate well during training, which is particularly important in models such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) where weight matrices are repeatedly multiplied. However, this experiment showed relatively high error rates, possibly due to the characteristics of the model used (simple MLP).

Problem with Scaled Orthogonal initialization: Scaled Orthogonal initialization showed a very high error rate at 2.30%. This suggests that this initialization method may not be suitable for the given model and dataset or requires additional hyperparameter adjustments. It is possible that the scaling factor was too small, causing learning to not occur properly.

L-Momentum Initialization Instability: L-Momentum had an error rate and convergence speed of nan and 0.00, which means that no learning occurred. The spectral norm being 20.30 is very high, which may be due to the weights’ initial values being too large, causing divergence.

Deep learning model initialization is a hyperparameter that should be carefully chosen considering the model’s architecture, activation functions, optimization algorithms, and characteristics of the dataset. The following are factors to consider when selecting an initialization method in practice.

Initialization is like a “hidden hero” in deep learning model training. Proper initialization can determine the success or failure of model training and plays a crucial role in maximizing model performance and reducing training time. Based on the guidelines presented in this section and the latest research trends, we hope you find the most suitable initialization strategy for your deep learning model.

Challenge: How can we address the issue of Gradient Descent getting stuck in local minima or having a slow learning rate?

Researcher’s Dilemma: Simply reducing the learning rate was not enough. In some cases, the learning became too slow and took a long time, while in other cases, it diverged and failed to learn. The path to finding the optimal point was as difficult as groping one’s way down a foggy mountain road. Various optimization algorithms such as Momentum, RMSProp, and Adam emerged, but there is still no single solution that perfectly fits all problems.

The remarkable progress in deep learning has been achieved not only through innovations in model architecture but also through the development of efficient optimization algorithms. The optimization algorithm is like a core engine that automates and accelerates the process of finding the minimum value of the loss function. How efficiently and stably this engine operates determines the learning speed and final performance of the deep learning model.

Optimization algorithms have evolved over the past few decades, solving three core challenges, much like living organisms evolve.

Each challenge has led to the birth of new algorithms, and the competition to find better algorithms continues to this day.

Recent optimization algorithms have evolved in the following three main directions. 1. Memory Efficiency: Lion, AdaFactor, etc., focus on reducing the memory usage required for training large models (especially Transformer-based ones). 2. Distributed Learning Optimization: LAMB, LARS, etc., increase efficiency when training large models in parallel using multiple GPUs/TPUs. 3. Domain/Task-Specific Optimization: Sophia, AdaBelief, etc., provide optimized performance for specific problem domains (e.g., natural language processing, computer vision) or specific model structures.

In particular, with the emergence of large language models (LLMs) and multimodal models, it has become even more crucial to efficiently optimize tens of billions of parameters, train in limited memory environments, and converge stably in distributed environments. These challenges have led to the development of new technologies such as 8-bit optimization, ZeRO optimization, and gradient checkpointing.

In deep learning, optimization algorithms play a core role in finding the minimum value of the loss function, i.e., finding the optimal parameters of the model. Each algorithm has its unique characteristics and pros and cons, and it is essential to choose the appropriate algorithm based on the characteristics of the problem and the structure of the model.

SGD and Momentum

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is the most basic and widely used optimization algorithm. At each step, it calculates the gradient of the loss function using mini-batch data and updates the parameters in the opposite direction.

Parameter Update Formula:

\[w^{(t)} = w^{(t-1)} - \eta \cdot g^{(t)}\]

Momentum is an improved method that introduces the concept of momentum from physics to SGD. By using the exponential moving average of past gradients, it gives inertia to the optimization path, mitigating the oscillation problem of SGD and increasing the convergence speed.

Momentum Update Formula:

\[v^{(t)} = \mu \cdot v^{(t-1)} + g^{(t)}\]

\[w^{(t)} = w^{(t-1)} - \eta \cdot v^{(t)}\]

The implementation code for the main optimization algorithms used in learning is included in the chapter_05/optimizer/ directory. The following is an example implementation of the SGD (including momentum) algorithm for learning purposes. All optimization algorithm classes inherit from the BaseOptimizer class and are implemented simply for learning purposes. (In actual libraries like PyTorch, they are implemented more complexly for efficiency and generalization.)

from typing import Iterable, List, Optional

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.basic import BaseOptimizer

class SGD(BaseOptimizer):

"""Implements SGD with momentum."""

def __init__(self, params: Iterable[nn.Parameter], lr: float,

maximize: bool = False, momentum: float = 0.0):

super().__init__(params, lr)

self.maximize = maximize

self.momentum = momentum

self.momentum_buffer_list: List[Optional[torch.Tensor]] = [None] * len(self.params)

@torch.no_grad()

def step(self) -> None:

for i, p in enumerate(self.params):

grad = p.grad if not self.maximize else -p.grad

if self.momentum != 0.0:

buf = self.momentum_buffer_list[i]

if buf is None:

buf = torch.clone(grad).detach()

else:

buf.mul_(self.momentum).add_(grad, alpha=1-self.momentum)

grad = buf

self.momentum_buffer_list[i] = buf

p.add_(grad, alpha=-self.lr)Adaptive Learning Rate Algorithms

Deep learning model parameters are updated with different frequencies and importance. Adaptive learning rate algorithms are methods that adjust the learning rate individually according to these parameter-specific characteristics.

AdaGrad (Adaptive Gradient, 2011):

Key Idea: Apply a small learning rate to frequently updated parameters and a large learning rate to infrequently updated parameters.

Formula:

\(w^{(t)} = w^{(t-1)} - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{G^{(t)} + \epsilon}} \cdot g^{(t)}\)

Advantage: Effective when dealing with sparse data.

Disadvantage: The learning rate decreases monotonically as learning progresses, which can cause learning to stop prematurely.

RMSProp (Root Mean Square Propagation, 2012):

Key Idea: To solve the learning rate decrease problem of AdaGrad, use an exponential moving average instead of the sum of past gradient squares.

Formula:

\(v^{(t)} = \beta \cdot v^{(t-1)} + (1-\beta) \cdot (g^{(t)})^2\)

\(w^{(t)} = w^{(t-1)} - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{v^{(t)} + \epsilon}} \cdot g^{(t)}\)

Advantage: The learning rate decrease problem is alleviated compared to AdaGrad, allowing for effective learning over a longer period.

Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation, 2014):

Adam is one of the most widely used optimization algorithms today, combining the ideas of Momentum and RMSProp.

Key Idea:

Formula:

\(m^{(t)} = \beta_1 \cdot m^{(t-1)} + (1-\beta_1) \cdot g^{(t)}\)

\(v^{(t)} = \beta_2 \cdot v^{(t-1)} + (1-\beta_2) \cdot (g^{(t)})^2\)

\(\hat{m}^{(t)} = \frac{m^{(t)}}{1-\beta_1^t}\)

\(\hat{v}^{(t)} = \frac{v^{(t)}}{1-\beta_2^t}\)

\(w^{(t)} = w^{(t-1)} - \eta \cdot \frac{\hat{m}^{(t)}}{\sqrt{\hat{v}^{(t)}} + \epsilon}\)

As the scale of deep learning models and datasets has exploded in recent years, there is a growing need for new optimization algorithms that support memory efficiency, fast convergence rates, and large-scale distributed learning. The following are some of the latest algorithms that have emerged to meet these demands.

Lion (Evolved Sign Momentum, 2023):

Sophia (Second-order Clipped Stochastic Optimization, 2023):

AdaFactor (2018):

Recent studies suggest that the algorithms introduced above (Lion, Sophia, AdaFactor) can exhibit superior performance to traditional Adam/AdamW under specific conditions.

Now, let’s try an experiment with 1 epoch to see if it works.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from dldna.chapter_04.models.base import SimpleNetwork

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_data_loaders, get_device

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.basic import Adam, SGD

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.advanced import Lion, Sophia

from dldna.chapter_04.experiments.model_training import train_model # Corrected import

device = get_device()

model = SimpleNetwork(act_func=nn.ReLU(), hidden_shape=[512, 64]).to(device)

# Initialize SGD optimizer

optimizer = SGD(params=model.parameters(), lr=1e-3, momentum=0.9)

# # Initialize Adam optimizer

# optimizer = Adam(params=model.parameters(), lr=1e-3, beta1=0.9, beta2=0.999, eps=1e-8)

# # Initialize AdaGrad optimizer

# optimizer = AdaGrad(params=model.parameters(), lr=1e-2, eps=1e-10)

# # Initialize Lion optimizer

# optimizer = Lion(params=model.parameters(), lr=1e-4, betas=(0.9, 0.99), weight_decay=0.0)

# Initialize Sophia optimizer

# optimizer = Sophia(params=model.parameters(), lr=1e-3, betas=(0.965, 0.99), rho=0.04, weight_decay=0.0, k=10)

train_dataloader, test_dataloader = get_data_loaders()

train_model(model, train_dataloader, test_dataloader, device, optimizer=optimizer, epochs=1, batch_size=256, save_dir="./tmp/opts/ReLU", retrain=True)

Starting training for SimpleNetwork-ReLU.Execution completed for SimpleNetwork-ReLU, Execution time = 7.4 secs{'epochs': [1],

'train_losses': [2.2232478597005207],

'train_accuracies': [0.20635],

'test_losses': [2.128580910873413],

'test_accuracies': [0.3466]}Lion is an optimization algorithm discovered by Google Research using AutoML techniques. Similar to Adam, it uses momentum, but its key feature is that it only utilizes the sign of the gradient, discarding the size information.

Key Ideas:

Mathematical Principles:

Update Calculation:

\(c_t = \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) g_t\)

Weight Update:

\(w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta \cdot \text{sign}(c_t)\)

Momentum Update:

\(m_t = c_t\)

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

References:

Sophia is an optimization algorithm that utilizes second derivative information (Hessian matrix) to improve learning speed and stability. Since directly computing the Hessian matrix is computationally expensive, Sophia estimates only the diagonal elements of the Hessian using an improved version of Hutchinson’s method.

Key Ideas:

Mathematical Principles:

| Description | |

|---|---|

| \(h_t\) | Estimate of the diagonal of the Hessian matrix at step \(t\). |

| \(z_t\) | Random vector used in Hutchinson’s method. |

| \(H_t\) | Hessian matrix at step \(t\). |

| \(\mathbb{E}[z_t z_t^T H_t]\) | Expected value of the product of \(z_t\), its transpose, and the Hessian \(H_t\). |

Hessian Diagonal Estimation:

At each step, a random vector \(z_t\) is sampled (\(z_t\)’s elements are chosen uniformly from {-1, +1}).

The estimate of the Hessian diagonal \(h_t\) is calculated as follows.

\(h_t = \beta_2 h_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_2) \text{diag}(H_t z_t) z_t^T\)

(where \(H_t\) is the Hessian at step t)

Sophia uses an exponential moving average (EMA) that leverages past estimates (\(h_{t-1}\)) to reduce the variance of Hutchinson’s estimator.

Update Calculation:

Weight Update:

\(w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta \cdot u_t\)

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

References:

AdaFactor is a memory-efficient optimization algorithm used for training large models, especially transformer models. It uses adaptive learning rates similar to Adam but improves the storage of second moments (variances) to significantly reduce memory usage.

Key Idea:

Mathematical Principle:

In Adam, the second-moment matrix \(v_t\) for an \(n \times m\) weight matrix requires \(O(nm)\) memory. AdaFactor approximates this matrix as follows.

Second-Moment Estimation:

$v_t = u_t v_{t-1} + (1 - u_t) g_t g_t^T$

where $u_t$ is the decay rate at step tUpdate Calculation:

\(m_t = \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) g_t\)

\(v_t = u_t v_{t-1} + (1 - u_t) g_t g_t^T\)

where \(\beta_1\) is the momentum decay rate and \(u_t\) is the second-moment decay rate

The update is calculated as \(u_t = m_t / \sqrt{v_t + \epsilon}\), where \(\epsilon\) is a small value for numerical stability.

Weight Update:

\(w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta \cdot u_t\)

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Update Calculation:

\(u\_t = g\_t / \sqrt{\hat{v\_t}}\)

Weight Update \(w\_{t+1} = w\_t - \eta \cdot u\_t\)

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

References:

The performance of optimization algorithms varies greatly depending on the task and model structure. Let’s analyze these characteristics through experiments.

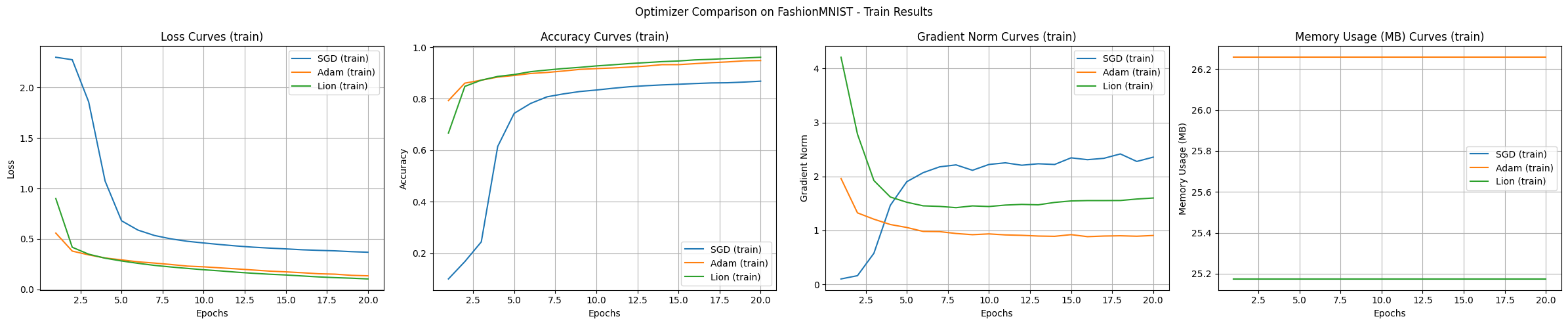

We compare basic performance using the FashionMNIST dataset. This dataset is a simplified version of actual clothing image classification problems, making it suitable for analyzing the basic characteristics of deep learning algorithms.

from dldna.chapter_05.experiments.basic import run_basic_experiment

from dldna.chapter_05.visualization.optimization import plot_training_results

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_data_loaders

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.basic import SGD, Adam

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.advanced import Lion

import torch

# Device configuration

device = torch.device("cuda:0" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Data loaders

train_loader, test_loader = get_data_loaders()

# Optimizer dictionary

optimizers = {

'SGD': SGD,

'Adam': Adam,

'Lion': Lion

}

# Optimizer configurations

optimizer_configs = {

'SGD': {'lr': 0.01, 'momentum': 0.9},

'Adam': {'lr': 0.001},

'Lion': {'lr': 1e-4}

}

# Run experiments

results = {}

for name, config in optimizer_configs.items():

print(f"\nStarting experiment with {name} optimizer...")

results[name] = run_basic_experiment(

optimizer_class=optimizers[name],

train_loader=train_loader,

test_loader=test_loader,

config=config,

device=device,

epochs=20

)

# Visualize training curves

plot_training_results(

results,

metrics=['loss', 'accuracy', 'gradient_norm', 'memory'],

mode="train", # Changed mode to "train"

title='Optimizer Comparison on FashionMNIST'

)

Starting experiment with SGD optimizer...

==================================================

Optimizer: SGD

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 23.0MB

Reserved: 48.0MB

Model Size: 283.9K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 27.2MB

Peak Reserved: 48.0MB

Current Allocated: 25.2MB

Current Reserved: 48.0MB

==================================================

Starting experiment with Adam optimizer...

==================================================

Optimizer: Adam

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 25.2MB

Reserved: 48.0MB

Model Size: 283.9K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 28.9MB

Peak Reserved: 50.0MB

Current Allocated: 26.3MB

Current Reserved: 50.0MB

==================================================

Starting experiment with Lion optimizer...

==================================================

Optimizer: Lion

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 24.1MB

Reserved: 50.0MB

Model Size: 283.9K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 27.2MB

Peak Reserved: 50.0MB

Current Allocated: 25.2MB

Current Reserved: 50.0MB

==================================================

The experiment results show the characteristics of each algorithm. The main observations from the experiments using the FashionMNIST dataset and the MLP model are as follows:

In the basic experiment, Adam and Lion showed rapid initial convergence speeds, Adam had the most stable learning, Lion used slightly less memory, and SGD tended to explore a wide range.

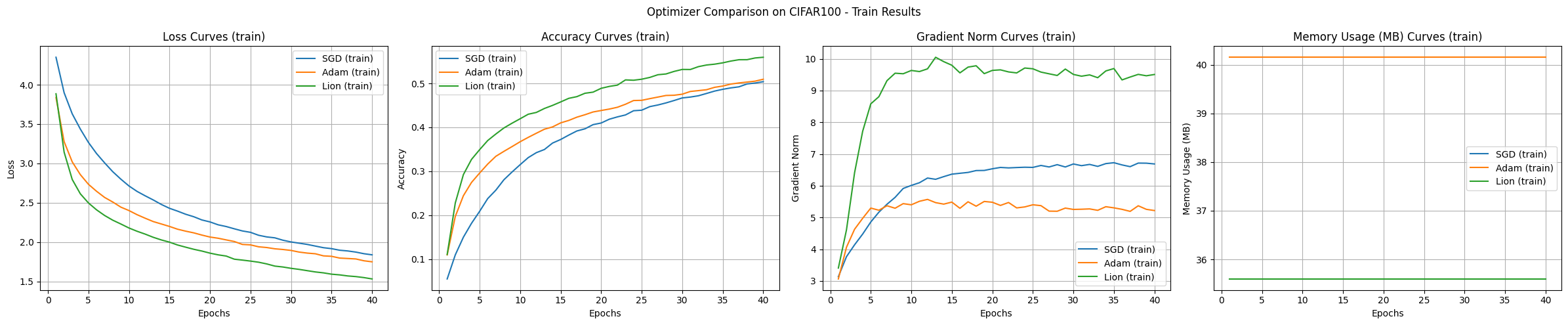

In CIFAR-100 and CNN/Transformer models, the differences between optimization algorithms become even more pronounced.

from dldna.chapter_05.experiments.advanced import run_advanced_experiment

from dldna.chapter_05.visualization.optimization import plot_training_results

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_data_loaders

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.basic import SGD, Adam

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.advanced import Lion

import torch

# Device configuration

device = torch.device("cuda:0" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Data loaders

train_loader, test_loader = get_data_loaders(dataset="CIFAR100")

# Optimizer dictionary

optimizers = {

'SGD': SGD,

'Adam': Adam,

'Lion': Lion

}

# Optimizer configurations

optimizer_configs = {

'SGD': {'lr': 0.01, 'momentum': 0.9},

'Adam': {'lr': 0.001},

'Lion': {'lr': 1e-4}

}

# Run experiments

results = {}

for name, config in optimizer_configs.items():

print(f"\nStarting experiment with {name} optimizer...")

results[name] = run_advanced_experiment(

optimizer_class=optimizers[name],

model_type='cnn',

train_loader=train_loader,

test_loader=test_loader,

config=config,

device=device,

epochs=40

)

# Visualize training curves

plot_training_results(

results,

metrics=['loss', 'accuracy', 'gradient_norm', 'memory'],

mode="train",

title='Optimizer Comparison on CIFAR100'

)Files already downloaded and verified

Files already downloaded and verified

Starting experiment with SGD optimizer...

==================================================

Optimizer: SGD

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 26.5MB

Reserved: 50.0MB

Model Size: 1194.1K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 120.4MB

Peak Reserved: 138.0MB

Current Allocated: 35.6MB

Current Reserved: 138.0MB

==================================================

Results saved to: SGD_cnn_20250225_161620.csv

Starting experiment with Adam optimizer...

==================================================

Optimizer: Adam

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 35.6MB

Reserved: 138.0MB

Model Size: 1194.1K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 124.9MB

Peak Reserved: 158.0MB

Current Allocated: 40.2MB

Current Reserved: 158.0MB

==================================================

Results saved to: Adam_cnn_20250225_162443.csv

Starting experiment with Lion optimizer...

==================================================

Optimizer: Lion

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 31.0MB

Reserved: 158.0MB

Model Size: 1194.1K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 120.4MB

Peak Reserved: 158.0MB

Current Allocated: 35.6MB

Current Reserved: 158.0MB

==================================================

Results saved to: Lion_cnn_20250225_163259.csv

The experimental results compare the SGD, Adam, and Lion optimization algorithms using the CIFAR-100 dataset and CNN model, showing the characteristics of each algorithm.

Convergence Speed and Accuracy:

Learning Curve Stability:

Memory Usage:

Gradient Norm:

Under the given experimental conditions, Lion showed the fastest convergence speed and highest accuracy. Adam demonstrated stable learning curves, while SGD was slow and had high variability. The memory usage was slightly lower for Lion and SGD compared to Adam.

from dldna.chapter_05.experiments.advanced import run_advanced_experiment

from dldna.chapter_05.visualization.optimization import plot_training_results

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_data_loaders

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.basic import SGD, Adam

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.advanced import Lion

import torch

# Device configuration

device = torch.device("cuda:0" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Data loaders

train_loader, test_loader = get_data_loaders(dataset="CIFAR100")

# Optimizer dictionary

optimizers = {

'SGD': SGD,

'Adam': Adam,

'Lion': Lion

}

# Optimizer configurations

optimizer_configs = {

'SGD': {'lr': 0.01, 'momentum': 0.9},

'Adam': {'lr': 0.001},

'Lion': {'lr': 1e-4}

}

# Run experiments

results = {}

for name, config in optimizer_configs.items():

print(f"\nStarting experiment with {name} optimizer...")

results[name] = run_advanced_experiment(

optimizer_class=optimizers[name],

model_type='transformer',

train_loader=train_loader,

test_loader=test_loader,

config=config,

device=device,

epochs=40

)

# Visualize training curves

plot_training_results(

results,

metrics=['loss', 'accuracy', 'gradient_norm', 'memory'],

mode="train",

title='Optimizer Comparison on CIFAR100'

)Files already downloaded and verified

Files already downloaded and verified

Starting experiment with SGD optimizer.../home/sean/anaconda3/envs/DL/lib/python3.10/site-packages/torch/nn/modules/transformer.py:379: UserWarning: enable_nested_tensor is True, but self.use_nested_tensor is False because encoder_layer.norm_first was True

warnings.warn(

==================================================

Optimizer: SGD

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 274.5MB

Reserved: 318.0MB

Model Size: 62099.8K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 836.8MB

Peak Reserved: 906.0MB

Current Allocated: 749.5MB

Current Reserved: 906.0MB

==================================================

Results saved to: SGD_transformer_20250225_164652.csv

Starting experiment with Adam optimizer...

==================================================

Optimizer: Adam

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 748.2MB

Reserved: 906.0MB

Model Size: 62099.8K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 1073.0MB

Peak Reserved: 1160.0MB

Current Allocated: 985.1MB

Current Reserved: 1160.0MB

==================================================

Results saved to: Adam_transformer_20250225_170159.csv

Starting experiment with Lion optimizer...

==================================================

Optimizer: Lion

Initial CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Allocated: 511.4MB

Reserved: 1160.0MB

Model Size: 62099.8K parameters

==================================================

==================================================

Final CUDA Memory Status (GPU 0):

Peak Allocated: 985.1MB

Peak Reserved: 1160.0MB

Current Allocated: 748.2MB

Current Reserved: 1160.0MB

==================================================

Results saved to: Lion_transformer_20250225_171625.csv

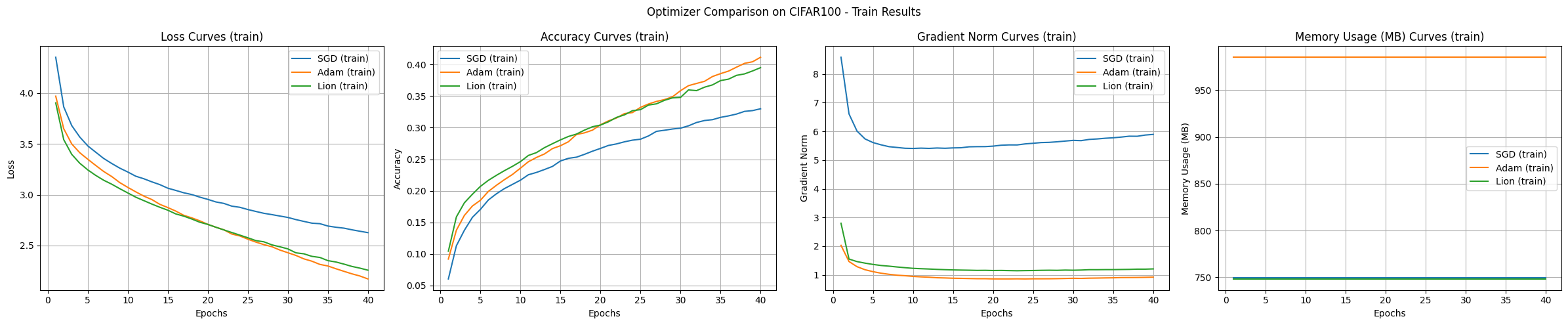

Typically, transformers are not used directly for image classification tasks, but rather in a structure modified to suit image characteristics, such as Vision Transformer (ViT). This experiment is conducted as an example for comparing optimization algorithms. The results of the transformer model experiment are as follows:

Conclusion In the experiment on the CIFAR-100 dataset, SGD showed the best generalization performance but had the slowest learning speed. Adam showed the fastest convergence and stable learning, but used a lot of memory, while Lion showed balanced performance in terms of memory efficiency and convergence speed.

Challenge: How can we effectively visualize and understand the deep learning optimization process that occurs in high-dimensional spaces with millions or tens of millions of dimensions?

Researcher’s Concern: The parameter space of deep learning models is a high-dimensional space that is difficult for humans to intuitively imagine. Researchers have developed various dimension reduction techniques and visualization tools to open this “black box,” but many parts still remain veiled.

Understanding the learning process of neural networks is essential for effective model design, optimization algorithm selection, and hyperparameter tuning. In particular, visualizing and analyzing the geometric properties of the loss function and the optimization path provide important insights into the dynamics and stability of the learning process. In recent years, research on loss surface visualization has provided a key to unlocking the secrets of neural network learning, contributing to the development of more efficient and stable learning algorithms and model structures.

This section examines the basic concepts and latest techniques of loss surface visualization and analyzes various phenomena that occur during the deep learning learning process (e.g., local minima, saddle points, characteristics of optimization paths). In particular, we focus on the impact of model structure (e.g., residual connections) on the loss surface and the differences in optimization paths according to optimization algorithms.

Loss surface visualization is a key tool for understanding the learning process of deep learning models. Just as a topographic map helps us understand the heights and valleys of mountains, loss surface visualization allows us to visually grasp the changes in the loss function in the parameter space.

In 2017, Goodfellow et al.’s study showed that the flatness of the loss surface is closely related to the model’s generalization performance. (Wide and flat minima tend to have better generalization performance than narrow and sharp minima.) In 2018, Li et al. used 3D visualization to show that residual connections make the loss surface flat, facilitating learning. These findings have become a core foundation for designing modern neural network architectures such as ResNet.

Linear Interpolation:

Concept: Linearly combine the weights of two different models (e.g., pre-/post-training models, models converged to different local minima) and calculate the loss function value between them.

Formula:

\(w(\alpha) = (1-\alpha)w_1 + \alpha w_2\)

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader, Subset

from dldna.chapter_05.visualization.loss_surface import linear_interpolation, visualize_linear_interpolation

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_dataset

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.metrics import load_model

# Linear Interpolation

# Device configuration

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Get the dataset

_, test_dataset = get_dataset(dataset="FashionMNIST")

# Create a small dataset

small_dataset = Subset(test_dataset, torch.arange(0, 256))

data_loader = DataLoader(small_dataset, batch_size=256, shuffle=True)

loss_func = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

# model1, _ = load_model(model_file="SimpleNetwork-ReLU.pth", path="tmp/models/")

# model2, _ = load_model(model_file="SimpleNetwork-Tanh.pth", path="tmp/models/")

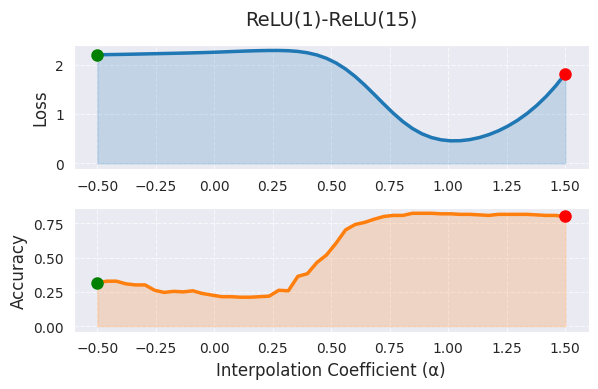

model1, _ = load_model(model_file="SimpleNetwork-ReLU-epoch1.pth", path="tmp/models/")

model2, _ = load_model(model_file="SimpleNetwork-ReLU-epoch15.pth", path="tmp/models/")

model1 = model1.to(device)

model2 = model2.to(device)

# Linear interpolation

# Test with a small dataset

_, test_dataset = get_dataset(dataset="FashionMNIST")

small_dataset = Subset(test_dataset, torch.arange(0, 256))

data_loader = DataLoader(small_dataset, batch_size=256, shuffle=True)

alphas, losses, accuracies = linear_interpolation(model1, model2, data_loader, loss_func, device)

_ = visualize_linear_interpolation(alphas, losses, accuracies, "ReLU(1)-ReLU(15)", size=(6, 4))

In linear interpolation, α=0 represents the weights of the first model (trained for 1 epoch), and α=1 represents the weights of the second model (trained for 15 epochs), while intermediate values represent a linear combination of the two models’ weights. The graph shows that as the value of α increases, the loss function value decreases, indicating that as training progresses, the model moves to a better optimum. However, linear interpolation has the limitation that it only shows a very limited cross-section of the high-dimensional weight space. The actual optimal path between the two models is likely to be nonlinear, and extending the range of α outside [0,1] makes interpretation difficult.

Using Bézier curves or splines for nonlinear path exploration, or PCA or t-SNE for visualizing high-dimensional structures, can provide more comprehensive information. In practice, it is recommended to use linear interpolation as an initial analysis tool and limit α to the range [0,1] or slight extrapolation. It should be analyzed comprehensively with other visualization techniques, and if there are large differences in model performance, further analysis is needed.

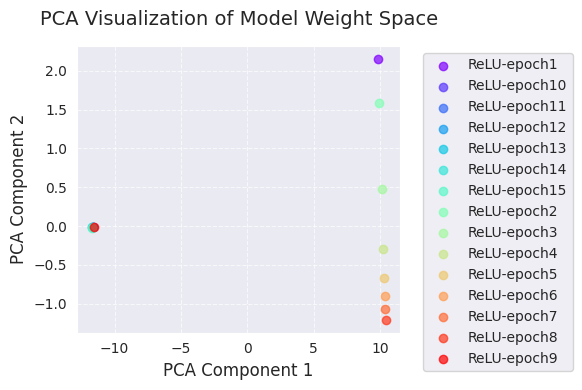

The following is the result of PCA and t-SNE analysis.

import torch

from dldna.chapter_05.visualization.loss_surface import analyze_weight_space, visualize_weight_space

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.metrics import load_model, load_models_by_pattern

models, labels = load_models_by_pattern(

activation_types=['ReLU'],

# activation_types=['Tanh'],

# activation_types=['GELU'],

epochs=[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]

)

# PCA analysis

embedded_pca = analyze_weight_space(models, labels, method='pca')

visualize_weight_space(embedded_pca, labels, method='PCA')

print(f"embedded_pca = {embedded_pca}")

# t-SNE analysis

embedded_tsne = analyze_weight_space(models, labels, method='tsne', perplexity=1)

visualize_weight_space(embedded_tsne, labels, method='t-SNE')

print(f"embedded_tsne = {embedded_tsne}") # Corrected: Print embedded_tsne, not embedded_pca

embedded_pca = [[ 9.8299894e+00 2.1538167e+00]

[-1.1609798e+01 -9.0169059e-03]

[-1.1640446e+01 -1.2218434e-02]

[-1.1667191e+01 -1.3469303e-02]

[-1.1691980e+01 -1.5136327e-02]

[-1.1714937e+01 -1.6765745e-02]

[-1.1735878e+01 -1.8110925e-02]

[ 9.9324265e+00 1.5862983e+00]

[ 1.0126298e+01 4.7935897e-01]

[ 1.0256655e+01 -2.8844318e-01]

[ 1.0319887e+01 -6.6510278e-01]

[ 1.0359785e+01 -8.9812231e-01]

[ 1.0392080e+01 -1.0731999e+00]

[ 1.0418671e+01 -1.2047548e+00]

[-1.1575559e+01 -5.1336871e-03]]

embedded_tsne = [[ 119.4719 -99.78837 ]

[ 100.26558 66.285835]

[ 94.79294 62.795162]

[ 89.221085 59.253677]

[ 83.667984 55.70297 ]

[ 77.897224 52.022995]

[ 74.5897 49.913578]

[ 123.20351 -100.34615 ]

[ -70.45423 -65.66194 ]

[ -65.55417 -68.90429 ]

[ -60.166885 -72.466805]

[ -54.70004 -76.077 ]

[ -49.00131 -79.833694]

[ -45.727974 -81.99213 ]

[ 105.22419 69.45333 ]]PCA and t-SNE visualizations project the change in the model weight space during training into a lower dimension (2D) to show it.

Through these visualizations, we can gain an intuitive understanding of the change in model weights during training and the weight space exploration of the optimization algorithm. In particular, using PCA and t-SNE together allows us to grasp both global changes (PCA) and local structures (t-SNE) simultaneously.

A contour plot is a method of visualizing the shape of the loss surface by drawing lines (contours) that connect points with the same loss function value on a 2D plane. Like the contours on a topographic map, it represents the “height” of the loss function.

The general procedure is as follows.

Setting the reference point: Select a reference model parameter (\(w_0\)). (e.g., parameters of a trained model)

Selecting direction vectors: Select two direction vectors (\(d_1\), \(d_2\)). These vectors form the basis of the 2D plane.

Perturbing parameters: Perturb the parameters around the reference point \(w_0\) along the selected two direction vectors \(d_1\), \(d_2\).

\(w(\lambda_1, \lambda_2) = w_0 + \lambda_1 d_1 + \lambda_2 d_2\)

Calculating loss values: For each combination of \((\lambda_1, \lambda_2)\), apply the perturbed parameters \(w(\lambda_1, \lambda_2)\) to the model and calculate the loss function value.

Contour plot: Use the \((\lambda_1, \lambda_2, L(w(\lambda_1, \lambda_2)))\) data to draw a 2D contour plot. (using functions like contour or tricontourf from matplotlib)

The contour map visually shows the local geometry of the loss surface and can also be used to analyze the behavior of optimization algorithms by displaying their trajectories.

import torch

import numpy as np

import torch.nn as nn

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader, Subset

from dldna.chapter_05.visualization.loss_surface import hessian_eigenvectors, xy_perturb_loss, visualize_loss_surface, linear_interpolation

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_dataset

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.metrics import load_model

from dldna.chapter_05.optimizers.basic import SGD, Adam

# Device configuration

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Get the dataset

_, test_dataset = get_dataset(dataset="FashionMNIST")

# Create a small dataset

small_dataset = Subset(test_dataset, torch.arange(0, 256))

data_loader = DataLoader(small_dataset, batch_size=256, shuffle=True)

loss_func = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

trained_model, _ = load_model(model_file="SimpleNetwork-ReLU.pth", path="tmp/models/")

# trained_model, _ = load_model(model_file="SimpleNetwork-Tanh.pth", path="tmp/models/")

trained_model = trained_model.to(device)

# pyhessian

data = [] # List to store the calculated result sets

top_n = 4 # Must be an even number. Each pair of eigenvectors is used. 2 is the minimum. 10 means 5 graphs.

top_eigenvalues, top_eignevectors = hessian_eigenvectors(model=trained_model, loss_func=loss_func, data_loader=data_loader, top_n=top_n, is_cuda=True)

# Define the scale with lambda.

lambda1, lambda2 = np.linspace(-0.2, 0.2, 40).astype(np.float32), np.linspace(-0.2, 0.2, 40).astype(np.float32)

# If top_n=10, a total of 5 pairs of graphs can be drawn.

for i in range(top_n // 2):

x, y, z = xy_perturb_loss(model=trained_model, top_eigenvectors=top_eignevectors[i*2:(i+1)*2], data_loader=data_loader, loss_func=loss_func, lambda1=lambda1, lambda2=lambda2, device=device)

data.append((x, y, z))

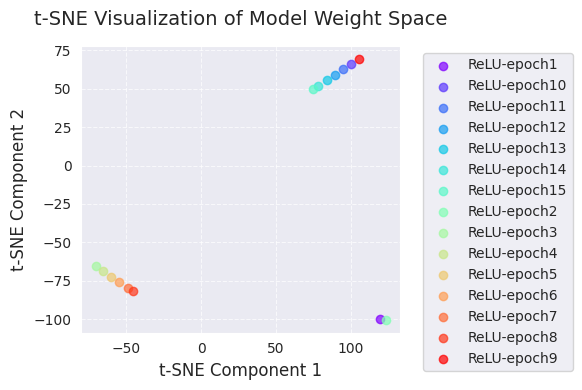

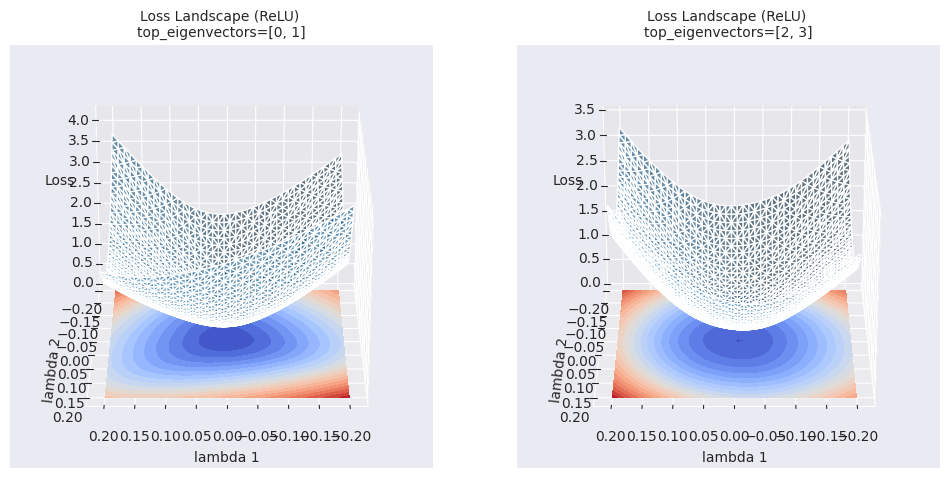

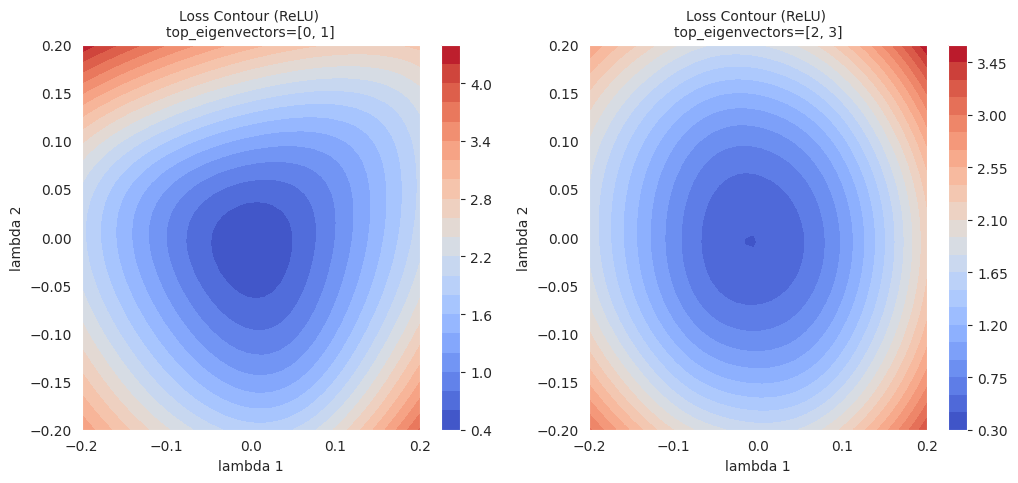

_ = visualize_loss_surface(data, "ReLU", color="C0", alpha=0.6, plot_3d=True)

_ = visualize_loss_surface(data, "ReLU", color="C0", alpha=0.6, plot_3d=False) # Changed "ReLu" to "ReLU" for consistency/home/sean/anaconda3/envs/DL/lib/python3.10/site-packages/torch/autograd/graph.py:825: UserWarning: Using backward() with create_graph=True will create a reference cycle between the parameter and its gradient which can cause a memory leak. We recommend using autograd.grad when creating the graph to avoid this. If you have to use this function, make sure to reset the .grad fields of your parameters to None after use to break the cycle and avoid the leak. (Triggered internally at ../torch/csrc/autograd/engine.cpp:1201.)

return Variable._execution_engine.run_backward( # Calls into the C++ engine to run the backward pass

Contour maps provide more detailed information about local areas than simple linear interpolation. While linear interpolation shows the change in loss function values along a one-dimensional path between two models, contour maps visualize the change in loss functions on a two-dimensional plane with the selected two directions (\(\lambda_1\), \(\lambda_2\)) as axes. This allows us to identify subtle changes in the optimization path, local minima in surrounding areas that could not be identified by linear interpolation, the existence of saddle points, and barriers between them.

Beyond simple visualization (linear interpolation, contour maps), advanced analysis techniques are being researched to gain a deeper understanding of the loss landscape of deep learning models.

Topological Data Analysis (TDA):

Multi-scale Analysis:

These advanced analysis techniques provide more abstract and quantitative information about the loss surface, contributing to a deeper understanding of the learning process of deep learning models and the establishment of better model design and optimization strategies.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn # Import the nn module

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader, Subset # Import DataLoader and Subset

from dldna.chapter_05.visualization.loss_surface import analyze_loss_surface_multiscale

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_dataset # Import get_dataset

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.metrics import load_model # Import load_model

# Device configuration

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Load dataset and create a small subset

_, test_dataset = get_dataset(dataset="FashionMNIST")

small_dataset = Subset(test_dataset, torch.arange(0, 256))

data_loader = DataLoader(small_dataset, batch_size=256, shuffle=True)

loss_func = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

# Load model (example: SimpleNetwork-ReLU)

model, _ = load_model(model_file="SimpleNetwork-ReLU.pth", path="tmp/models/")

model = model.to(device)

_ = analyze_loss_surface_multiscale(model, data_loader, loss_func, device)

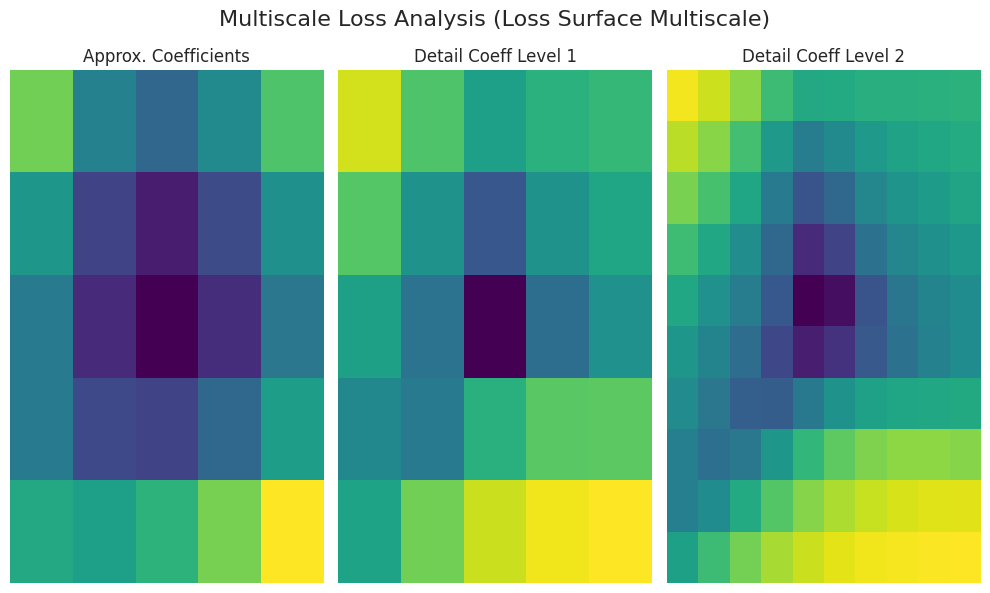

The analyze_loss_surface_multiscale function was used to analyze and visualize the loss surface of the SimpleNetwork-ReLU model trained on the FashionMNIST dataset from a multi-scale perspective.

Graph Interpretation (Wavelet Transform-Based):

Approx. Coefficients: Represents the overall shape (global structure) of the loss surface, likely with the minimum value at the center (low loss values).

Detail Coeff Level 1/2: Shows smaller scale changes. “Level 1” represents medium-scale and “Level 2” represents the finest-scale undulations (local minima, saddle points, noise, etc.).

Color: Dark colors (low loss), bright colors (high loss)

The results may vary depending on the implementation of the analyze_loss_surface_multiscale function (wavelet function, decomposition level, etc.).

This visualization shows only part of the loss surface and it is difficult to fully grasp the complexity of high-dimensional space.

Multi-scale analysis decomposes the loss surface into multiple scales, revealing a multi-layered structure that is difficult to discern through simple visualization. By understanding large-scale tendencies and small-scale local changes, it helps to understand optimization algorithm behavior, learning difficulty, generalization performance, etc.

Topology is a field of study that examines geometric properties that do not change under continuous transformations. In deep learning, topology-based analysis is used to analyze topological features such as connectivity, holes, and voids of the loss surface, providing insights into learning dynamics and generalization performance.

Key Concepts:

Sublevel Set: For a given function \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) and threshold \(c\), it is defined as \(f^{-1}((-\infty, c]) = {x \in \mathbb{R}^n | f(x) \leq c}\). In the context of loss functions, it represents the region of parameter space with a loss value below a certain threshold.

Persistent Homology: Tracks changes in sublevel sets and records the creation and destruction of topological features (0th: connected components, 1st: loops, 2nd: voids, …).

Persistence Diagram: A plot of the birth and death values of each topological feature on a coordinate plane. The \(y\)-coordinate (\(\text{death} - \text{birth}\)) represents the “lifetime” or “persistence” of the feature, with higher values indicating more stable features.

Bottleneck Distance: A method for measuring the distance between two persistence diagrams. It finds the optimal matching between points in the two diagrams and calculates the maximum distance between matched points.

Mathematical Background (Brief):

Application to Deep Learning Research: * Loss Surface Structure Analysis: Through persistence diagrams, we can understand the complexity of the loss surface, the number of local minima, stability, and the presence of saddle points. * Example: Gur-Ari et al., 2018 calculated the persistence diagram of neural network loss surfaces, showing that wide networks have a simpler topological structure than narrow networks. * Generalization Performance Prediction: The characteristics of persistence diagrams (e.g., the lifetime of the longest-lived 0-dimensional feature) may be correlated with the model’s generalization performance. * Example: Perez et al., 2022 proposed a method to predict the generalization performance of models using persistence diagram characteristics. * Mode Connectivity: We find paths connecting different local minima and analyze the energy barriers on these paths. * Example: Garipov et al., 2018

References:

The loss surface of deep learning models has various scale features. From large-scale valleys and ridges to small-scale bumps and holes, various geometric structures of different sizes affect the learning process. Multi-scale analysis is a method for separating and analyzing these various scale features.

Key Idea:

Wavelet Transform: The wavelet transform is a mathematical tool that decomposes a signal into frequency components of various frequencies. When applied to the loss function, it can separate features of different scales.

Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT):

\(W(a, b) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) \psi_{a,b}(x) dx\)

Mother Wavelet: A function that satisfies certain conditions (e.g., Mexican hat wavelet, Morlet wavelet) (see reference [2] for details)

Multi-Resolution Analysis (MRA): A method for discretizing the CWT to decompose a signal into different resolution levels.

Mathematical Background (Brief):

Application to Deep Learning Research:

Loss Surface Roughness Analysis: Wavelet transforms can be used to quantify the roughness of the loss surface and analyze its effect on learning speed and generalization performance.

Optimization Algorithm Analysis: Analyzing how optimization algorithms move along features at each scale can help better understand their behavior.

References: 1. Mallat, S. (2008). A wavelet tour of signal processing: the sparse way. 2. Daubechies, I. (1992). Ten lectures on wavelets. 3. Li, Y., Hu, W., Zhang, Y., & Gu, Q. (2019). Multiresolution analysis of the loss landscape of deep nets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.00779.

The actual loss surface of deep learning models exists in ultra-high-dimensional space, ranging from millions to tens of billions of dimensions, and has a very complex geometric structure. Therefore, directly visualizing and analyzing it is virtually impossible. Additionally, the actual loss surface has various problems such as non-differentiable points, discontinuities, and numerical instability, making theoretical analysis difficult.

Using the loss surface approximated by a Gaussian function, let’s visualize how the optimizer works in a 2D plane.

Please provide the original Korean text for translation. I will translate it into English according to the given instructions.

# Gaussian fitting

popt, _, offset = get_opt_params(x, y, z)

gaussian_params = (*popt, offset)

# Calculate optimization paths

points_sgd = train_loss_surface(

lambda params: SGD(params, lr=0.1),

[d_min, d_max], 100, gaussian_params

)

points_sgd_m = train_loss_surface(

lambda params: SGD(params, lr=0.05, momentum=0.8),

[d_min, d_max], 100, gaussian_params

)

points_adam = train_loss_surface(

lambda params: Adam(params, lr=0.1),

[d_min, d_max], 100, gaussian_params

)

# Visualization

visualize_optimization_path(

x, y, z, popt, offset,

[points_sgd, points_sgd_m, points_adam],

act_name="ReLU"

)The graph shows the learning paths of three optimization algorithms, SGD, Momentum SGD, and Adam, on a loss surface approximated by a Gaussian function. The three algorithms show different characteristics in both gentle and steep areas.

In practice, Momentum SGD is much more preferred than SGD itself, and adaptive optimization algorithms like Adam or AdamW are also widely used. Generally, the loss surface tends to be flat in most areas but has a narrow and deep valley shape near the minimum value. Therefore, a large learning rate can cause overshooting or divergence, so it is common to use a learning rate scheduler that gradually decreases the learning rate. Additionally, it is essential to consider not only the choice of optimization algorithm but also an appropriate learning rate scheduler, batch size, regularization techniques, and more.

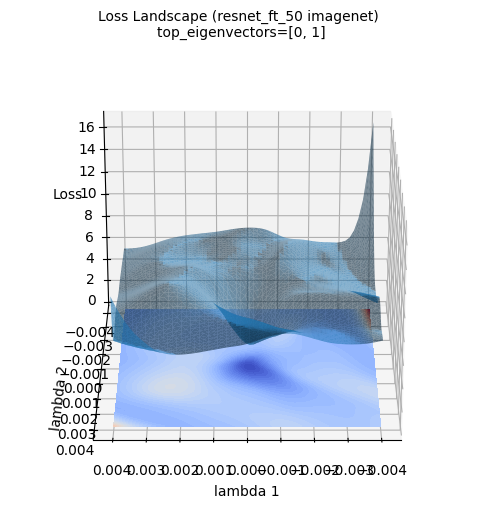

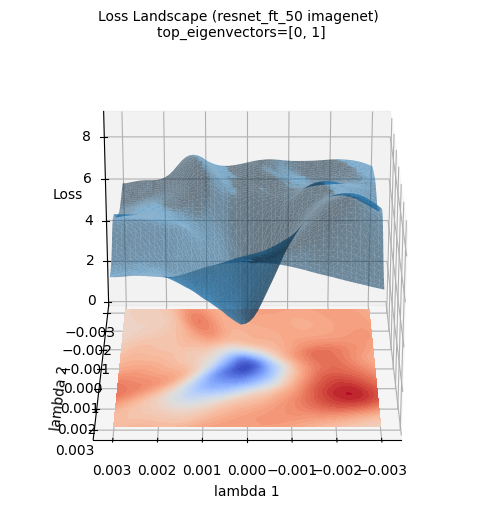

The above loss surface image is a 3D visualization of the loss surface of a ResNet-50 model newly trained on the ImageNet dataset (using the top two eigenvectors of the Hessian matrix calculated by PyHessian as axes). Unlike the Gaussian function approximation, the actual loss surface of deep learning models has a much more complex and irregular shape. Nevertheless, it can be seen that the large tendency for the minimum value to exist in the central area (blue area) is maintained. This visualization helps provide an intuitive understanding of how complex the actual loss surface of deep learning models is and why optimization is a difficult problem.

Understanding how optimization algorithms navigate through the loss landscape to find the minimum value in deep learning model training is crucial. Especially with the emergence of large language models (LLMs), analyzing and controlling the learning dynamics of models with billions of parameters has become even more important.

The deep learning model training process can be divided into initial, mid-term, and late stages, each with its own characteristics.

Stage-wise Characteristics:

Layer-wise Gradient Characteristics:

Parameter Dependencies:

Optimization Path Analysis:

To analyze the stability of the optimization process, consider the following:

Gradient Diagnostics:

Hessian-based Analysis:

Real-time Monitoring:

Gradient Clipping: Limit the gradient size (norm) to not exceed a threshold.

\(g \leftarrow \text{clip}(g) = \min(\max(g, -c), c)\)

\(g\): gradient, \(c\): threshold

Adaptive Learning Rate: Adam, RMSProp, Lion, Sophia, etc. automatically adjust the learning rate based on gradient statistics.

Learning Rate Scheduler: gradually decrease the learning rate based on the training epoch or validation loss.

Hyperparameter Optimization: automatically search and adjust optimization-related hyperparameters.

Recent (2024) studies on learning dynamics are advancing in the following directions:

These studies contribute to making deep learning model training more stable and efficient and help to understand the “black box”.

Now, let’s explore the dynamic analysis of the optimization process through a simple example.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.optim as optim

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader, Subset # Import Subset

from dldna.chapter_05.visualization.train_dynamics import visualize_training_dynamics

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.data import get_dataset

from dldna.chapter_04.utils.metrics import load_model

# Device configuration

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Load the FashionMNIST dataset (both training and testing)

train_dataset, test_dataset = get_dataset(dataset="FashionMNIST")

train_loader = DataLoader(train_dataset, batch_size=256, shuffle=True)

loss_func = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

# Load a pre-trained model (e.g., ReLU-based network)

trained_model, _ = load_model(model_file="SimpleNetwork-ReLU.pth", path="tmp/models/")

trained_model = trained_model.to(device)

# Choose an optimizer (e.g., Adam)

optimizer = optim.Adam(trained_model.parameters(), lr=0.001)

# Call the training dynamics visualization function (e.g., train for 10 epochs with the entire training dataset)

metrics = visualize_training_dynamics(

trained_model, optimizer, train_loader, loss_func, num_epochs=20, device=device

)

# Print the final results for each metric

print("Final Loss:", metrics["loss"][-1])

print("Final Grad Norm:", metrics["grad_norm"][-1])

print("Final Param Change:", metrics["param_change"][-1])

print("Final Weight Norm:", metrics["weight_norm"][-1])

print("Final Loss Improvement:", metrics["loss_improvement"][-1])The example above actually shows various aspects of the learning dynamics described. Using a pre-trained SimpleNetwork-ReLU model on the FashionMNIST dataset and continuing to train it with the Adam optimization algorithm, we visualized the following five key metrics for each epoch:

The graph shows the following:

Through this example, we can visually confirm the process of the optimization algorithm minimizing the loss function, the change in gradients, and the change in parameters, and gain an intuitive understanding of the learning dynamics.

In this chapter 5, we deeply explored various topics related to optimization, a key element of deep learning model training. We understood the importance of weight initialization methods, the principles and characteristics of various optimization algorithms (SGD, Momentum, Adam, Lion, Sophia, AdaFactor), and loss surface visualization and learning dynamics analysis to better understand the training process of deep learning models.

In chapter 6, we will learn about regularization, a key technique for improving the generalization performance of deep learning models. We will examine the principles and effects of various regularization techniques such as L1/L2 regularization, dropout, batch normalization, and data augmentation, and learn how to apply them through practical examples.

SGD Manual Calculation:

Gradient Descent Convergence Speed Comparison:

Initialization Method Comparison:

Adam Optimizer:

Batch Normalization and Initialization:

Lion Optimizer Analysis:

c_t = β_1 * m_{t-1} + (1 - β_1) * g_t w_{t+1} = w_t - η * sign(c_t) m_t = c_t

Initialization Method Experiment:

Optimization Path Visualization: